We all know someone who has an idea, a misconception, we think is ridiculous. They can be about almost any topic – some that get media attention are ideas like the Earth is flat, people never landed on the Moon, or vaccines cause autism. Some idiots even think there is a worldwide network of Satan-worshipping child traffickers run by the Clintons, and Donald Trump is going to save them all.

What is a misconception?

Misconceptions are beliefs which contradict current scientific views. And they aren’t just confined to strange conspiracies. We can also hold misconceptions in exercise and nutrition too… in fact, they’re common, because we all have some personal experience with our exercise or our diets that inform our opinions. But this may not guide us to a correct understanding of what happens in our bodies.

We call these misconceptions, instead of mistakes or errors, because we may hold these beliefs despite access to good information, and the chance to correct them. And in the conspiracy theories I just mentioned, there is plenty of good information proving them wrong!

Why do some of us hold these misconceptions, and others don’t? How can we be sure our knowledge is accurate? How can we identify or correct misconceptions? And how common are misconceptions about fitness and nutrition?

Today we explore some research that answers these questions. As far as we know it’s the first research looking to solve these issues in the fitness industry.

What misconceptions in exercise and nutrition are we talking about?

There has been some research about these misconceptions in the past, often using university students, and more complex information. We wanted to investigate personal trainers, vocational students, and the public. So the misconceptions will be different, and from different sources.

First we interviewed educators. We spoke to experts at several universities, and lecturers in vocational fitness courses, on their opinions of popular misconceptions in exercise and nutrition.

We wanted to know what misconceptions they came across in students. And we wanted to know what information, and teaching strategies, they would use to correct these.

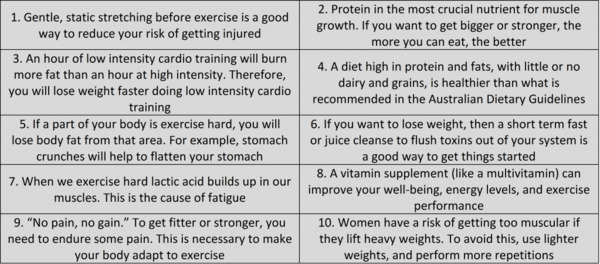

During these interviews, we decided on 10 misconceptions, which you can see in the table below.

The misconceptions in exercise and nutrition statements used in this research. Some are more controversial than others!

But some of these are not misconceptions!

You may disagree with some of these, which is ok. It’s possible our wording was unclear in places. We used this survey to examine misconceptions in both professionals and the public. So compromises in language and detail were needed, and some meaning could have been lost. We live and learn…

And maybe changing evidence can mean some of these misconceptions become out of date. Even the experts didn’t agree all the time. But most did, most of the time. And most of the disagreements were about small details.

Strangely, the one misconception most unclear in the research was, in my opinion at the time, the least controversial. But some recent research has shown there may be a reduced risk of injury with static stretching before exercise! I was so surprised to find this out that I wrote about it.

If you disagree that any of these are misconceptions for other reasons, you think we got it wrong, or you’re ahead of the science, that’s ok! It could be you know something I don’t. Or it could be you need to read this helpful guide about how to argue against a scientific consensus.

Go for it Internet, tell me what we got wrong. How bad could it be?

The research

Once we decided on our misconceptions, we created a survey that asked if people agreed with these statements, and some similar factual statements. We also asked about the sources of exercise and nutrition information people used, their trust of those sources, and did a simple test of critical thinking ability.

What does critical thinking have to do with exercise and nutrition?

Great question. Critical thinking is defined as “reasonable reflective thinking”. We think it’s important, as people can reject information, and explanations, that conflict with their opinions and values.

So just providing correct information isn’t enough. But maybe people who are more willing to reflect on, and assess their own knowledge, are more willing to adjust their opinions.

For these people, we don’t need to correct every myth they come across. They can identify their own lack of knowledge, assess the source of information, and identify the need for better information if it’s needed. They can prevent misconceptions forming without our help!

Who were our participants?

We surveyed a range of different students and professionals, with different types of qualification. At university level, we surveyed 1st and 3rd year exercise science students from Curtin University, as well as graduate exercise professionals.

For comparison, we surveyed members of the public with no relevant qualifications.

What did we find?

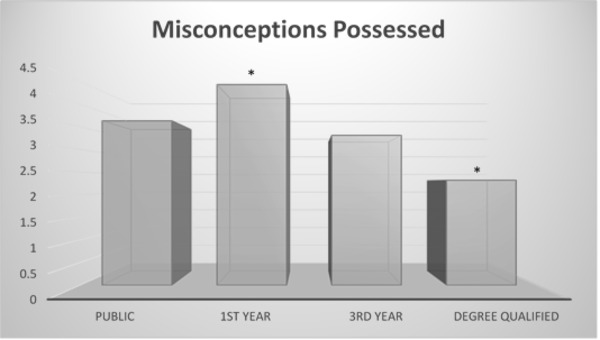

As you would expect, those who were further into their education had fewer misconceptions. 3rd year students had fewer misconceptions than 1st year students. And professionals had fewer again.

The difference in misconceptions of exercise and nutrition in the public, students, and degree qualified professionals. * Represents a significant difference to all other groups

But we also see that members of the public had fewer misconceptions than first year students. Why is that?

Why did people hold misconceptions?

There are a few factors associated with fewer misconceptions. As we expected to see, one was critical thinking ability. Another was more trust in reliable sources of information.

So was the level of qualification a person held. But this was any qualification, not just exercise science degrees!

In this case, our general public group was highly educated, and scored highly in our test of critical thinking ability. So they may not represent the average person as much as we would like. But without exercise science degrees they could identify misconception statements (or at least identify that they didn’t know the correct answer!)… this is another hint that it’s the skills of learning, like critical thinking ability, rather than the facts we learn, that are important here.

The ability to learn is crucial! These skills may protect us more from misconceptions than what we learn!

The most common misconceptions were “lactic acid causes fatigue” (half our professional group agreed with this), “a vitamin supplement can improve your well-being…” (over 40% in all groups), “no pain, no gain” (over 50% in all groups except the professionals), and “the more protein, the better”. In this last case, our third-year group performed better than the other. Perhaps our degree qualified participants were a bit rusty in their knowledge of metabolism!

Misconceptions in personal trainers and fitness students

We wanted to look at personal trainers too, but as they usually have different qualifications, we looked at them separately to our degree qualified group.

In Australia, vocational fitness students complete a Certificate IV in Fitness (sometimes with a lower-level Certificate III course as well). This usually takes less than a year. So we had the opportunity to assess the same students at the beginning and the end of their qualification.

We wanted to see if their critical thinking ability, or the number of misconceptions they possessed, changed during the course. We then compared these students to practicing personal trainers.

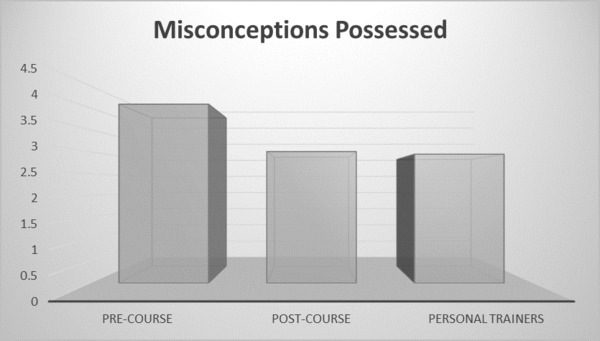

Misconceptions in vocational fitness students, and vocationally qualified personal trainers. The pre-course student group had more misconceptions than the other two groups

Students possessed fewer misconceptions at the end of the course compared to the beginning. This is great to see! Some professionals speak quite poorly of these qualifications, but here we see their education had a positive impact.

But there was no difference between students at the end of their course, and experienced personal trainers.

In other words, our personal trainers, with an average of 6 years of experience, held just as many misconceptions as students. So the problem may not be with the quality of these courses, but the quality of the professional development trainers do once they’re working in fitness.

How did these results compare to those doing degrees?

There were some similarities with our earlier groups. Again, critical thinking ability and the level of education achieved (any education), was associated with fewer misconceptions. But having a higher exercise qualification (like a diploma instead of a Certificate IV) did not help.

Trust in reliable sources of information was also associated with fewer misconceptions, while trust in less reliable sources (like friends, social media, magazines, and alternative health practitioners) was associated with more misconceptions.

Like previous research into the fitness industry, there was no relationship between the experience of trainers, and agreement with either factual or misconception statements. An experienced trainer may not be a more knowledgeable trainer.

The same misconceptions were popular in these groups as in the previous groups, with the addition of “static stretching reduces injury risk”, which was popular in both pre-course students (76%), and personal trainers (37%), but not post-course students.

How can we correct misconceptions in exercise and nutrition?

As we mentioned earlier, research shows us that people will interpret information that agrees with their current opinions differently to what they disagree with.

Information they agree with is seen as more reliable and convincing. So just providing good information may not be enough to change someone’s mind. But if we could improve the skills of critical thinking we may be able to help people correct these misconceptions themselves.

For the last part of this project we designed an online course that aimed to improve the critical thinking skills of personal trainers.

At the end of the course, the personal trainers who took part changed in the following ways:

- Performance in the critical thinking test improved

- The number of misconceptions they possessed reduced

- Trust in reliable sources was increased

- Trust in less reliable sources was decreased

This is encouraging, as it tells us that instruction in critical thinking may help correct misconceptions in fitness. And this could be useful if someone is stubbornly rejecting information they don’t agree with!

A screenshot from Critical Thinking for Fitness Professionals. In this example we were talking about how to have a collaborative argument, rather than an adversarial one. The topic being argued was interval training.

Where to from here?

We found out that misconceptions decrease as someone completes an exercise qualification, which is great. But personal trainers do not continue to improve once they graduate.

There are two possible explanations. Either the professional development trainers take part in is not helping to prevent or correct misconceptions, or trainers do not do enough professional development.

Given the high turnover of trainers in the fitness industry, it may be a little of both. Some trainers may not see the point in staying up to date because they don’t see a long-term future in the industry. Others may make not seek to challenge themselves, and select information they will already agree with. Or they may attend more diverse training but reject information they disagree with.

Attending professional development when a misconception is challenged may be a little like this. Don’t reject new information immediately. If it’s wrong, find out why. What is the quality of the evidence backing it up?

Long term solutions

Firstly, we need to include specific instruction in critical thinking in personal training courses. Thankfully, in Australia at least, this has already begun. A new personal training qualification is now being developed. New personal trainers will need to know how to identify evidence-based sources of information, and to be able to critically reflect on their own knowledge and practice. It’s a huge first step!

Secondly, we should encourage trainers to seek out higher level qualification, like degrees, rather than rely on vocational qualifications. This benefits everyone. Trainers learn new skills and make themselves more employable. Clients get more knowledgeable trainers.

Finally, we need resources to help trainers, students, and members of the public to make better decisions about exercise and nutrition information. Not everyone has the skills to interpret high-quality sources of information, like academic research. So qualified science communicators, providing explanations and context, have a valuable role.

Here at Critical Fitness, we try to help out with this last point. We not only want to inform people about exercise and nutrition, we want to change the way people think about exercise and nutrition, and the sources of information they use.

Updates:

This article was originally published in June 2019. I updated it in January 2021 with links to my published research, and to make it (hopefully) a more enjoyable read.

Recent Comments