Personal training and pre-exercise screening – these things should go hand-in-hand. We shouldn’t have one without the other. Every trainer should be doing a great, detailed screening with their clients, but many don’t.

This is because as a trainer you probably want to get to the first session with a new client as soon as possible. In fact, the first time you even meet a client may be their first training session… learning about the new client as they go.

Today we look at what should happen instead… once you take on a new client, and before the first training session.

I understand why this part of the process is neglected. Many trainers have turnover of clients that mean they want someone to get started as soon as possible. They need money.

And most trainers don’t charge for a pre-exercise screening. They don’t want to waste time on this before they can get into a session and can start making many.

Sounds stressful, doesn’t it?

Personal trainers should conduct a detailed pre-exercise screening, but many don’t

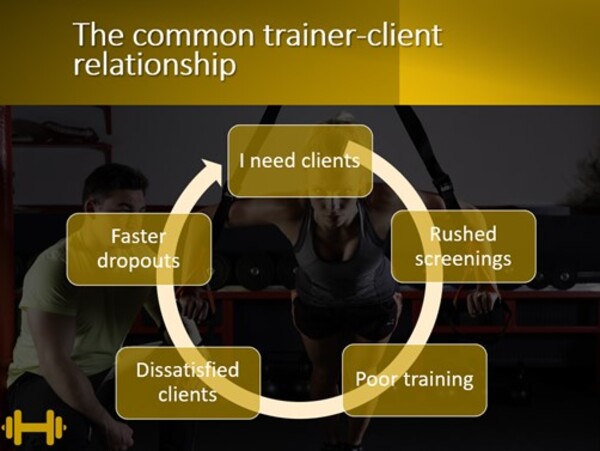

The common personal trainer/client relationship

Imagine this scenario… you have said “yes” to a new client and want to get them started as soon as you can, for the reasons discussed above. So you get straight into the first training session. The idea here is to find out about the client as you go and modify the training on the fly.

And because you are a reasonably competent trainer, it goes ok. But it could have gone better. Even the best trainers in this situation will have to change a lot of weights and exercises, and you are no different. You get some intensities wrong. The client stands around a little too much while you make your adjustments… and they feel that the session hasn’t quite hit the mark.

It’s hard to get good, honest feedback in this scenario. The client says they enjoyed it, and worked reasonably hard, but they didn’t sound enthusiastic.

You get the feeling that this professional relationship won’t last long…

Sometimes these relationships stop through no fault of either party. Many clients aren’t a great match to the style of exercise a trainer offers, or their personality, even if they do try to meet their needs.

But in this case, you could have done better. And because you notice this lack of enthusiasm from the client, you don’t try as hard with this client, instead focusing on the clients you think are better long-term propositions. The client notices, and it’s only a matter of weeks until they drop out.

There must be a better way for trainers to retain clients

Don’t worry, there is.

The problem here is the hustle to get new clients training is not only a result of low client retention, but also a cause of low client retention. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

You rush your process with new clients, the training suffers, and clients drop out. You aren’t meeting clients’ needs, you haven’t gained their confidence and trust, and they aren’t happy with the service. Clients notice when you cut corners…

The lack of a good pre-exercise screening can lead to faster client dropout. Trainers beware!

Then you are looking for a new client again!

Instead, what I propose is you devote more time and energy to screening a new client, not less. Be attentive to their needs, go above and beyond when you meet them, and you are more likely to retain them. In a crowded gym full of potential clients, and trainers doing a half-arsed job, this work ethic is your best advertisement.

During my time as a full-time trainer, I found that the most common way I attracted clients was not word of mouth, or advertising, or introductory offers. It was people watching how I worked with a client.

Someone would be watching the trainers in the gym, forming an opinion about who they wanted to work with. And they would pick me more than any other trainer. Not because I was the biggest, or the strongest, or looked the best, or smiled the most. I was none of these things. But I was attentive to my clients.

And this attention starts with the pre-exercise screening…

The pre-exercise screening

For many, the pre-exercise screening is a chance to meet the client and cover the essentials. A bit of a chat, complete some paperwork, then see you next week for a session!

These trainers don’t charge anything for this, because it’s worthless.

Instead, you should see this as a valuable chance to get to know the client well, and understand their motivations, abilities, barriers, and attitudes. In my opinion the better you are as a trainer, the more you will want to know about your client before you start throwing weights at them.

Talk to the client, listen to them, watch them move, test them, and agree to a plan. Your pre-exercise screening should be the longest appointment you have with a client. And you should charge for it. Because if you do it well, it has enormous value.

Here’s what you should be doing in your first session with a new client:

Step 1: get to know the client

It sounds obvious, doesn’t it? But a lot of us don’t do it well. Get to know them. Have a chat, it doesn’t need to be all about the exercise. Hopefully you will start to like and respect each other. But even if you don’t like the client, they will start to like you as you show an interest in them.

I see too many trainers pushing a hard sell in their pre-exercise screening. They spend this first appointment making the client know how good they are, how great the training will be, what benefits they can get. They talk up the results their other clients get, and say “yes” to everything, like we described above.

But some people are put off by this approach.

And when you are putting on the hard sell, you aren’t listening to the client. You aren’t letting them speak. This is the only way to find out about them.

I like to let my client talk without interrupting or steering the conversation. Even if we go off topic. I can always take a note of something important that came up, and circle back later. In the meantime, everyone loves talking about themselves. Everyone! So let them!

This conversation is a chance for the client to relax, which can be crucial if they are hesitant about personal training. Gyms are intimidating if you don’t know if it’s the right place for you or not. So a friendly face and a sympathetic ear can go a long way if the client feels this way.

Step 2: find out about their history

Once you’ve had some idle chat, you’re ready to get into specifics. Now we can ask about the things we really need to know to train our client safely, and effectively.

We can break this up into three main areas.

Exercise history

Find out as much as possible here. What sports have they played? How long ago? What incidental exercise do they do? Gardening, walking their dog, playing with the kids, it all counts as exercise.

If they’ve done structured exercise in a gym (or with a trainer) before, I want even more detail. What exercises do they remember doing? What weights can they lift? How were their sessions structured? How far and hard did they run?

I might even want to know what they enjoyed about their previous training, and what they didn’t… though how much this will play into my programming will depend on how motivated by results they are!

Injury history

As important as what exercise the client can do, is what they can’t do.

If a client has exercised before, they will have an injury history. Maybe short and incidental, maybe long and debilitating. We need to know about it, and how to work around it.

Many personal trainers feel constrained by their scope of practice here… they think there is too much they can’t do when a client is injured. After all, you can’t diagnose an injury, prescribe therapeutic exercise, or treat it in any way.

But by asking the right questions, you will be surprised by how much you can achieve.

For example… if a client has an overuse injury, they we probably treated by a physiotherapist. The physio probably gave them advice on how to manage and rehabilitate the injury. If they can tell you what that was, you can incorporate this advice into your planning.

Even if you don’t have a diagnosis, you can work around it. Chronic back pain, for example, often has no clear medical cause, and can come and go throughout our lives. But the client can probably tell you what hurts, and what doesn’t, if it’s even related to exercise at all. No one knows the client’s pain like they do, and we can work with them to avoid causing pain.

And sometimes, as we get someone moving more and getting stronger, this type of pain goes away. We’ve fixed them, and we’ve stayed within our scope of practice.

It would be ideal if we can contact the professional that treated our client, and ask questions, but that’s unlikely. And some clients won’t go to a physiotherapist no matter how much we ask. So find out how to work around the pain.

Medical history

Again, we often don’t need to know all the details of a medical condition, depending on the impact on exercise. And again, we can get plenty of useful information from the client.

And again, we can apply some judgement. I’ve seen newly qualified trainers send someone to their doctor when their blood pressure as low as 143/80, when they assessed them at 3pm on a weekday. They’re following the rule outlined in their textbook, but they’re not applying common sense.

For example, they could make sure the client is relaxed and comfortable, then test them again. And find out more about their day… did they have coffee before they came in? A cigarette? Were they driving in heavy traffic? Have they had a stressful day? Are they nervous about being in a gym?

There are times when we can use our professional judgement, and not waste the client’s time and money.

But if we identify someone as a high-risk client, this is when we don’t muck around with personal judgements… send them to their doctor, and request guidance or a medical clearance.

If your client doesn’t want to do this, you don’t want to train them! They clearly have a different assessment of risk than you do, and this is something you don’t want to expose yourself to. Be brave enough to walk away from this client, and you will avoid a headache later.

Step 3: understand the client’s why and how

This is really underrated. Lots of trainers talk about goals. Fewer ask their clients why these goals are important.

For example, I can’t remember how many times a client has told me they want to “tone up a little”, or “get a bit fitter”.

But when I ask more questions, they’re not sure why. They sometimes just think it’s the right thing to say, because they’re in a gym chatting to a trainer. They could be telling us what they think we want to hear.

Sometimes people start exercising with minimal amount of motivation. They think they need to do something, but they’re not sure what. They’ve been told it’s good for them, but it’s still not something they really want to do yet.

By understanding this we can make sure the exercise we propose for the clients matches their beliefs, abilities, preferences, and motivations. This means our clients will stay with us for longer and commit more to the exercise. When it comes to getting the best outcome for our clients, this is key.

So, this discussion needs to be driven by the client. It should be a free-flowing discussion, where we ask questions, and listen to the answers. We should ask open questions, getting client to explain and elaborate, not a series of yes or no questions.

Whatever you do, don’t limit the goal setting part of the screening to a few tick boxes on a document – I’ve seen this many times before. Fitting the client into some convenient categories makes it easier for us but does a disservice to the client!

What type of goal are we looking for?

We usually think about goals in terms of outcomes. Particularly in fitness, when we might want to see a number on the scales, a weight lifted, a distance run, etc.

But these sorts of goals aren’t always useful for achieving lasting behaviour change. If we are trying to change behaviour, why aren’t we making that behaviour our goal?

And unlike outcomes, or behaviour is more within our control. Despite what some celebrity trainers will tell you, health and weight loss are complex and multifaceted. There are people who don’t achieve what we consider a realistic goal, despite their best efforts.

But these same people could sustain behaviour change that involves more incidental exercise, even if their weight doesn’t change. They could make better food choices that improve their health. They could join a community sport team, or participate in group exercise, and get the benefits that this social support provides.

These types of goals are known as process goals. And for many of our clients, they are a more appropriate choice. For us as trainers they could be better too, because they don’t rely on the client achieving a certain number, which they may not achieve for reasons out of our control.

Step 4: assess the client

By now you’ve probably been chatting for quite a while. We’ve probably started to form an idea about how our sessions are going to look. But we still need to know more before we can plan some good training for them…

Movement screening

A priority for me is seeing how my clients move. I have some standard movements that I start with when screening a client, like a squat, a lunge, a push up, and a pull. You can make different choices if you like, they just need to be movements that can be used to inform your exercise programming later.

After a standard assessment, you can select other movements based on the client. If the client will need power movements, you might look at them jumping and landing. For shoulder mobility, you might look at an overhead squat. If they’ve had a knee injury, you might look at a single leg squat on each leg.

If these movements look good, you know you can load these, or similar movements, straight away. But if they look weak, unsteady, or restricted, I need to hold back a little. We might be using body weight, light dumbbells, or even machine weights.

If I’m not sure that I can safely program exercise for this person due to pain or restriction, this is another referral opportunity.

Strength and fitness testing

My movement screening can tell me what exercises to program, and if I can apply load. Strength and fitness testing can now tell us how much load to apply.

Many rookie trainers choose an exercise to test as a way of assessing clients’ progress against their goals… especially if they’ve chosen an outcome goal, as discussed above.

And while that can be useful, it doesn’t always help us plan better sessions. Test exercises that help you program the weights clients will lift.

For example, a one-rep max squat helps program weight for a range of lower body exercises (not just squats), as our strength in these exercises have a relationship we can predict. In the same way, a bench press helps program upper body exercise.

Fitness testing will depend a lot on what mode of exercise your clients need. For example, when training football and cricket athletes we usually used a 2km time trial.

And in the same way someone’s strength in a squat can help us predict the weight we could program for a lunch, a client’s speed over 2km can help us predict their speed over 500m, for example. So, a trainer could program target times for cardio training, and be very accurate with their intervals…

…however many trainers are far more into lifting weights than they are running in my experience, so few do this well!

Nutrition assessment

This may or may not be necessary, depending on the needs of the client. But even the decision not to do a nutrition assessment is one you should be able to justify.

And if you need to do a nutrition assessment, what sort of assessment? Personal trainers are heavily restricted by their scope of practice here. But that doesn’t mean they can’t provide helpful, detailed advice for most people, particularly around healthy eating and weight management.

Some nutrition assessments can be very simple, like a food frequency questionnaire. These can be great if you think a client may have a diet that is very restrictive. Others are more detailed, like a 24-hour food recall, and require detailed follow-up questions.

And if this isn’t enough to meet a client’s needs (though it will be most of the time), we need to be able to refer to someone we can trust, like an accredited dietitian, who can help.

A personal trainer’s nutrition scope of practice can include basic healthy eating advice around servings, sizes, suggested snacks, etc.

Step 5: decide on the plan

Now you have all the preliminaries out of the way, we need to plan our training. Best practice here is to give the client a say in how this is put together. This helps you plan the training in a way that suits their schedule and preferences, but also gives the client more autonomy around their training.

Self-determination theory tells us that autonomy, a feeling of being in control of your own actions, leads to better long term exercise adherence. And as we all know, this leads to better client outcomes.

It’s possible that for the client to really buy in to a program, we need to make some compromises… about training volume, intensities, and even the types of exercise we choose.

This can be frustrating, but it’s worth it. Why? Because any program a client follows, no matter how bad, is better than a program they don’t follow. We can always develop and progress our programs over time, as our clients learn to trust what we’ve put in place for them.

Session planning

Once you have your plan in place, you can start to plan individual sessions in a way that is consistent with this plan. Some trainers will plan more than others, depending on experience, familiarity with the client, and whether sessions are in person. But it’s something I always recommend for new trainers.

And the underpinning knowledge that informs this planning should be informed by high quality evidence. This starts with your formal education, where course material should be based on solid scientific evidence (though this isn’t guaranteed).

It continues with the professional development choices you make. You should rely on material that is up-to-date, created by highly credentialed professionals, and consistent with the broader body of scientific evidence. You could try to read some of this research yourself, but it’s very hard to read without specific research training.

But research isn’t everything, of course. Just like no battle plan survives contact with the enemy, no session plan will survive contact with a difficult client in a crowded gym. There are lots of compromises we need to make on the spot. Exercises change, the order of them changes, the way we apply load will change. A great trainer can make all these changes, with minimal compromise to how effective the session is.

Summing Up

If I want you thinking one thing by this stage of the article, it is “wow, personal training is more complicated than I thought”.

At its best, personal training is a complex decision-making process. You are constantly making choices, even if your choice is sometimes not to train with someone, or not to use a particular option. Often these choices are intuitive and quick, based on your previous experience and preferences as a trainer. But they should be deliberate and slow, consider our reasons, and helping us to make better choices.

If you put this amount of effort into your screening and decision making, your client should also quickly realise how hard you are working to provide them with the best, most effective service possible.

And the best thing is, it’s all within your scope of practice! We’re not trying to diagnose injuries, treat chronic illness, align chakras, or train the “superficial spiral line”. *

Unfortunately, many trainers don’t put this amount of effort into their screening. Many don’t do a screening at all. Some use an online form involving some tick boxes. That’s better than nothing, but not by much.

A screening is a rich, information gathering process, for both the trainer and the client. The trainer is learning how to provide the best service possible. And the client is learning about the trainer’s diligence and attention to detail.

It’s the first step to establishing a productive, trusting, long-term professional relationship.

* Or whatever other brand of horseshit you want to make up

Recent Comments