Today we discuss one of the most enduring misconceptions about exercise – the idea that children lifting weights will have their growth stunted.

You might have been told this when you were a child. Maybe you told this to someone else. You probably passed this idea along as fact, with only have the vaguest idea of why you thought this, and even less idea about whether it was true.

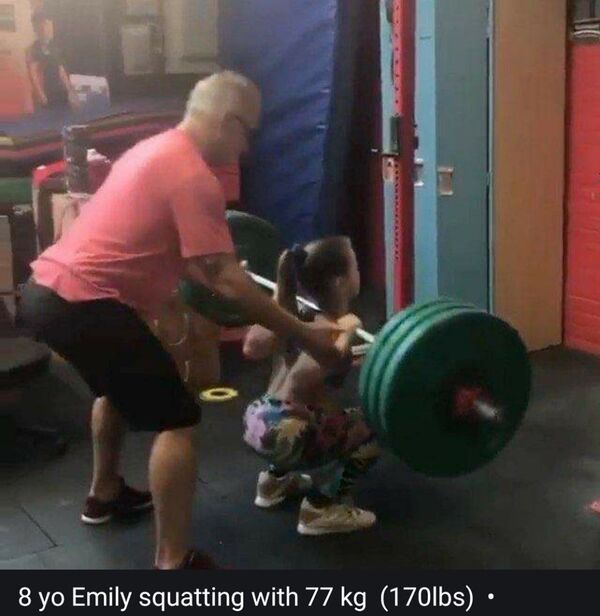

This article was inspired by a video I saw on social media recently (a screenshot is below). My eyes lit up, and I went straight to the comments, expecting a rich source of misconceptions to discuss. I was not disappointed.

Emily squatting 80kg like it’s no trouble at all. Some people don’t have a squat this good at 28, let alone 8 years old!

I tried to find out more information about this video, because the numbers are impressive! But I couldn’t find the original source. I can’t confirm that the weight is correct, or even if the video has not been altered. If you know more, let me know.

But if it is fake, it still exposes our biases and misconceptions.

If it is a real video, the child is a lifting prodigy! And it allows us to discuss the concept of children lifting weights, and our reactions to it.

What were commenters saying about this child lifting weights this heavy?

Some expressed a general sense of unease. They weren’t quite sure what the problem was, but they knew they didn’t like it. Some of you will feel this too, even if you are a fan of resistance training.

Then there were some comments that were the worst kind of incoherent sexism. I think the person below was concerned that this girl will become too manly if she lifts weights. Or something like that. I tried to come up with the best possible version of this guy’s meaning for the sake of a misconception to discuss, but I’m stumped.

If a woman or a girl wants to life weights, they can lift as heavy as they want. They won’t “get too big”, “look too manly”, or any other criticism you might have heard before.

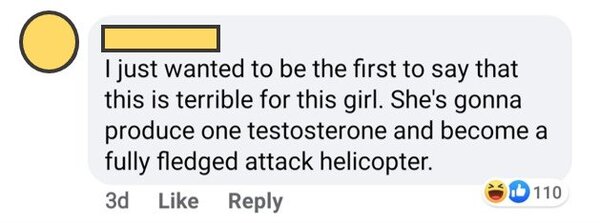

A child lifting weights will damage their bones!

The most common reaction was reciting a jumble of assorted misconceptions concerning sealing growth plates and stunting her growth, or causing arthritis.

As I mentioned above, these commenters are mostly misinformed. To discuss why, we will start with an anatomy lesson…

The anatomy of our bones

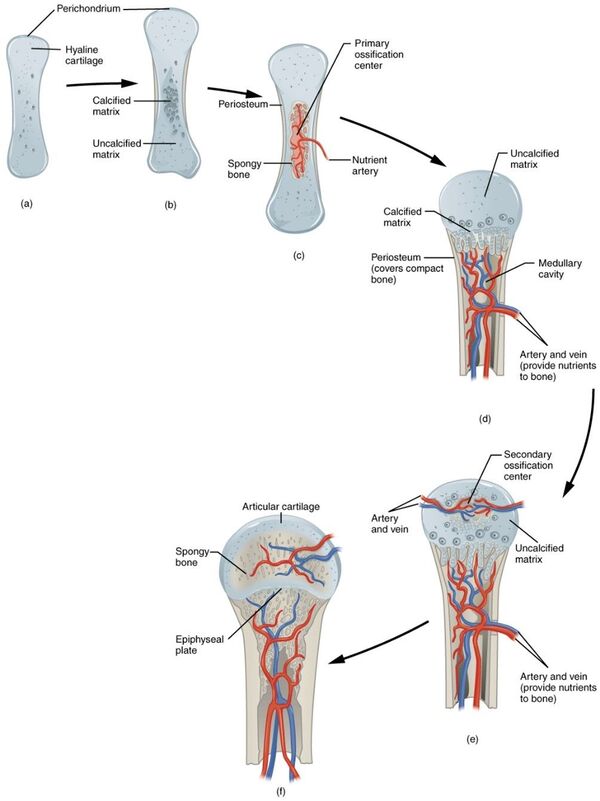

The long bones of our body consist of a hollow shaft, filled with marrow. The walls of this shaft are made of dense, compact bone. At each end is spongy bone, which looks like a 3-dimensional lattice.

And between these is the epiphysial plate, known as the growth plate. This is where cartilage is produced, eventually becoming ossified – turned into solid bone. When we stop growing, this plate gets sealed, and no new bone is produced.

Our bones change as they grow

As an embryo our bones are entirely cartilage. Bone starts growing after about six or seven weeks as this cartilage ossifies, and we build more bone from undifferentiated connective tissue.

By the time we are born, most of the cartilage is gone. Some remains around the ends of the joint (the articular cartilage).

The changing shape, and replacement of cartilage by hard bone during our development in the womb. Photo from openstax.

But this doesn’t mean they stop changing. Of course, our bones continue to thicken and lengthen as we grow.

They also change in shape. In our hips, for example, the head of the femur becomes longer, and sits deeper in our pelvis. And the socket in our pelvis becomes deeper to accommodate this.

Our bones also change in response to the stimulus we place on them. When someone lifts weights, or goes for a run, they apply extra load to these bones. This stimulates cells called osteoblasts, which produce new bone. So the next time we are exposed to a stimulus like this, we are a bit stronger, and more robust.

When we are less active, however, this process is reversed. Bone becomes less dense in the lack of this stimulus, and our bones become more brittle. As we age then, exercise, and particularly resistance training, is crucial to our bone health. We can maintain our bone density for longer, and reduce our risk of fractures and falls as we age.

Injury rates for lifting weights

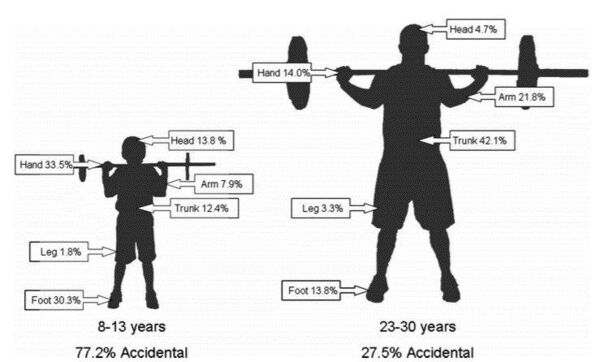

The pattern of injury changes as we age. We are more likely to see muscle strains for example, increasing from 18% of injuries in 8 to 13-year-olds presenting to emergency departments, to 66% in 23 to 30-year-olds.

Conversely, two-thirds of injuries in 8 to 13-year-old children were from weights being dropped, or body parts getting pinched in equipment.

The pattern of injuries in adults and young people, from Myer et al. (2009).

And while these numbers look at the proportions of injuries, we have no need to be concern about overall risk. Weights training is safer than many other activities we take part in, as either children or adults.

For some reason, lifting weights has attracted this stigma, and not some of these other activities.

Could we cause arthritis later in life by lifting weights when we are young?

Again, there is no evidence that children lifting weights will lead to osteoarthritis later in life.

In fact, adults with arthritis can get significant benefit from resistance training, without any increase in their pain. In fact, their pain may decrease, and ability may improve.

Could children seal their bones’ growth plates when lifting weights?

It’s understandable how this fear came about… growth plates can be three to five times weaker than surrounding tissue. An adolescents have a higher injury risk here than adults, particularly during growth spurts. But this is not specific to lifting weights.

Injuries to growth plates have been reported from lifting weights and examined in the scientific research. But these are rare, and mostly only case studies. And these injuries mostly occurred in the distal radius and ulna (just above the wrist), not the back, hips, or leg.

What was the cause of these growth plate injuries? Usually a lack of supervision! The children either lifted an inappropriate weight or behaved in a way that exposed themselves to injury.

When young people are well supervised in the gym, these injuries rarely happen. And there is no evidence that the height of children and adolescents is negatively impacted from lifting weights.

The takeaway here? Make sure training is supervised by qualified professionals, prescribing appropriate exercises and loads, progressing at an appropriate weight.

Jumping, landing, and contact in sport exposes young people to high forces. But many of us encourage this, while discouraging lifting weights in a controlled, supervised setting. Why?

What are the benefits for young people lifting weights?

In fact, not only is lifting weights safe, but it is recommended! There are many benefits of lifting weights for young people.

For a start, there are the usual changes in body composition, insulin sensitivity, and bone density we also see in adults. And in sport we see improved sports performance, and reduced injury risk, just like in adults.

But we also see general motor skills also improve. In other words, we can be more coordinated as we learn how to move our body safely with load. At an age when our physical skills can develop rapidly, this is important.

We can see improvements in self-efficacy and body image. While these may not be as important for some of us, for an adolescent finding their way in the world, this can do wonders for their confidence.

And finally, perhaps even most importantly, we lay the foundation for a habit of lifelong physical activity.

Are there any real dangers from lifting weights at this age?

Weights training in generally safe. When injuries do occur in children, they are due to a lack of supervision, unqualified supervision, or inappropriate loads.

The major danger here is not from lifting weights. It is burnout.

We see this all the time with child prodigies. And this child is clearly very gifted. And a child this gifted will often be super successful when compared to her peers. We see not just the child, but the parents get a bit too excited. They then push her into specialist training programs to develop her ability.

But we see this associated with greater injury risk, and higher rates of dropout, than if the child had a more regular sporting childhood and specialised later in life. The idea that specialising early allows our child to develop their talent better, is outdated now.

Long-term athletic development is better if we delay specialisation

This early specialisation is a bigger danger than the weight she is lifting.

Regardless of how talented children are, they should be encouraged sample widely from a variety of sports, developing general “physical literacy”. This creates more durable, well-rounded athletes later in life.

We now know that these children will probably become more successful in their sport as adults. And they’ve had a more rounded education in sport, experience both success and failure, and learning to cope with each. They have played sport for fun and enjoyment, as well as success and achievement.

In fact, this approach is now embedded into the long-term athletic development models that national sporting organisations use around the world.

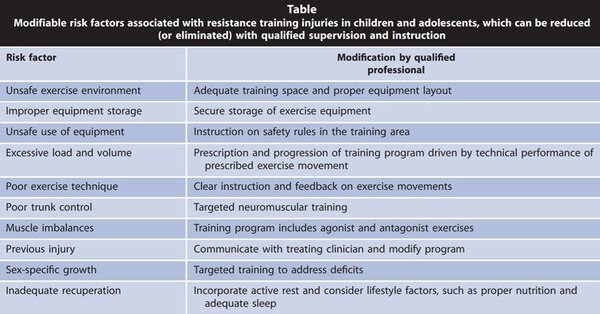

How else can we reduce injury risk?

Mostly by being sensible. Weights and exercise choices will usually be more conservative because the children are still learning the movements. And as they will be more active than adults, and growing, we need to allow enough sleep and recovery for our exercising children.

Well-qualified exercise professionals should be able to program safe resistance training for children. Table from Faigenbaum et al., 2011.

And we see the abilities of our children change as they mature, in ways which are no cause for alarm. Children will find their mobility decrease as their bones change shape. They will go through growth spurts until late adolescence, which can change the mechanics of their movement significantly.

This will lead to them seeming to go backwards at times. But it’s a normal part of growth, and something we allow for in models of long-term athletic development.

Recent Comments