There’s been a recent systematic review of physiotherapy practices. We like to think that when we see a health professional we get good quality advice, but we don’t always know. Do physiotherapists provide evidence-based treatment? We’d like to think so!

Are we getting the best help possible? Or something that is outdated, less effective, or even going to make things worse?

We recently came across this review when discussed by the lead author in a piece on The Conversation. It was interesting enough that we wanted to cover it further!

We often expect some physical, hands-on treatment from a physiotherapist, and if we don’t get it, we might be disappointed. But how often is this the best available approach to your issue?

Physios spend most of their time with clients working to improve their movement through recovering from injury, and managing pain. They use a variety of techniques. You may get advice about managing training loads, or have corrective exercise or mobility movements prescribed. They may use a range of different equipment, including some such as ultrasound and electrotherapy, which are a little controversial.

We want to make sure when we receive treatment from a professional, we are getting the most effective, cheapest options. So the authors of this study put together all the research they could find about the evidence-based practices of physios when providing musculoskeletal care, to find out how widespread poor practices were.

But you’re not a physiotherapist!

That’s right. So we needed some expert commentary on this paper, and reached out to New Zealand physiotherapist Aaron Marshall. Aaron has a Bachelor degree in physiotherapy, and is often called upon to provide expertise to insurers, and in the legal system, about the appropriateness of treatments. And of course, he’s a physiotherapist that provides evidence-based treatment whenever he can.

He starts us off by looking at the encouraging signs to come out of this research.

Let’s look at the good, the bad, and the ugly from this article. The good thing is that physiotherapists use recommended care more often than some other primary health care professionals.

Unfortunately, this means the numbers for other professionals aren’t that great. When you see a general practitioner, you are getting recommended care about 57% of the time.

Does this mean doctors are not evidence-based?

Not at all. Nor does it that mean half of doctors are incompetent. Sometimes you are getting care this is still effective, just not the best choice. And recommendations change quickly in some areas, so doctors may not always be up to date with the newest recommendations.

Other professionals are much more mixed. In chiropractic for example, about half of final year students said chiropractic could help the immune system, make childbirth easier, and improve the health of infants. We know none of this is even remotely true.

But Aaron still feels the need for improvement.

The bad – we can always do better. This is not a Meatloaf song, and only two out of three is bad.

Meat Loaf would be happy with level of recommended care from physiotherapists, but we think we can always do better! “IMG_7736” (CC BY 2.0) by rufusowliebat

In what areas were physiotherapists not providing evidence-based treatment?

We not only want to strive for better than two out of three, but 27% used treatments not based on evidence at all, or recommended against. That compares well to the chiropractors mentioned above. And they’re almost certainly better than personal trainers, given the errors in knowledge, and poor sources of information frequent in the fitness industry. But we’re not happy with those odds!

Some areas were worse than others. One of the main complaints we’d see a physio for – lower back pain – only had a 35-50% rate of recommended treatment choices. Recommended care includes reassurance that most people recover without treatment, and encouragement and advice on staying active and self-management.

The authors report this number could be lower due to the inclusion of some older studies that don’t reflect current advice, and incomplete treatment notes by physios (which were the basis of many of the studies in the review).

Then there’s the ugly. Aaron was pretty blunt here.

Magnetic field therapy. Need I say more?

Sometimes physios might recommend total nonsense – much like half of chiropractors! Some physios recommended acupuncture or traction for lower back pain, and magnetic field therapy was strangely popular for shoulder pain. These are currently recommended against, along with TENS and ultrasound machines you may have seen used in physio clinics previously, but are less common these days.

What can we conclude about physiotherapy treatment from this?

Aaron gave us some guidance on how to interpret these findings.

Everyone wants treatment that meets the highest standards and (rightly) expects this from their trusted physiotherapist. But the realities are often a little different.

Remember that the clinical model has changed in the last 40 years. We now take more whole person view of symptoms and impairments associated with different conditions (called a biopsychosocial approach). This means that some treatment might not be recommended care, but can meet the need for patient in front of the clinician at that time.

There is, however, a difference between treatment provided to address a specific impairment or issue, which may not be best practice (e.g. manual therapy for neuromodulation of chronic pain), and treatment shown to have a negative effect on rehabilitation (e.g. bed rest in lower back pain).

This is important. Physiotherapy, along with other allied health professions, is now more aware that the client is not the sum of their muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones. They are treating a person. Our confidence in our body, and our practitioner, is crucial.

Physiotherapy is changing as our evidence changes

A great example of this is recent change in the way non-specific, chronic lower back pain is managed. None of the biomedical approaches to managing back pain have been shown to be much better than any other. Many sufferers reporting multiple failed treatments, conflicting advice, and eventual loss of hope that their condition will improve.

Back pain sucks. But new approaches by physiotherapists are proving to be more effective than traditional treatment options.

A much broader approach is now being used more often, led by physios such as Professor Peter O’Sullivan, from Curtin University. There is now a push for decreasing the amount on hands-on therapy used. More physios focus on managing a patient’s psychological distress, changing fear and avoidance behaviour, and improving self-efficacy through coping strategies.

Previously, for example, we may have worried about “instability” in the lower back. It’s now known that guarded movement, co-contraction of trunk muscles, and an inability to relax are common in those with this type of pain. So some of the advice previously given (and still recommended by many personal trainers) may have been counterproductive.

So what should you look for when seeing a physiotherapist?

The take-home message is to check that your treatment is from recommended guidelines and only supplemented with well-explained alternatives. While you might not know what these guidelines are (it’s not like there is a public list) as a general rule, this should include;

- Education – understandable and positively focused, to ensure that you know exactly what is causing your problem and what you can do about it.

- Goal setting – so that treatment is focused on achieving what is important to you.

- Advice on activities/exercise – guidance towards activities that are positive and helpful to your condition.

- Treatment – aimed at improving your symptoms and independence.

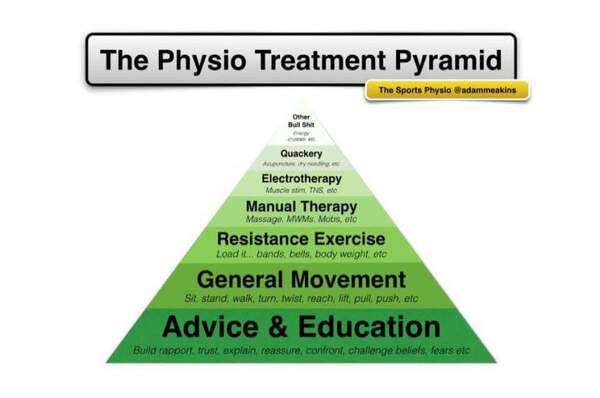

Aaron thinks there may still be a place for some treatments that are not best practice, as long as best practice is still used when possible. UK physio Adam Meakins agrees, and suggests in the graphic below (and in much of his writing) that education and encouraging reasonable activity form the bulk of a physio’s treatment options.

Adam Meakins, aka The Sports Physio, provides some advice on what’s important, and what’s peripheral, in the physiotherapist’s tool kit.

Sometimes there is a place for quackery and other bullshit, but the bulk of treatment should be the guidelines that Aaron outlines above.

If your treatment is not like this, ask about the recommended care and a more active, exercise-based approach. This puts the power of recovery in your hands, or with some collaboration, the hands of your exercise professional.

This is exactly why the profession of physio is not taken seriously. This article is such a shallow attempt to offer a much-needed critical discussion on PT, but others as well. There is so much low value treatment that props up the PT business model, so little evidence supporting the profession, it’s kind of scary. Stuck in the past, has done little except talk up a storm with practices still used as if in a time machine from 1960s. Overpriced, overhyped education, few optionsbotherv5han processing bodies which gets tedious after you come to realize how much of a scam the various gurus have pushed. And then there are the electro-modalities, oodles more useless garbage. Zero critical thinking, followers of the faith.

Thanks for commenting Marie. As you rightly identify, there are some treatments still used by some practitioners with little evidence to support them. Thankfully this is changing, though like all change it is slow, and at times painful.

However, keep in mind that compared to other some other allied health fields (chiropractic, for example), physiotherapy compares well. At least, that is what the research so far tells us.

I am not defending any therapy or discipline, including chiros, PTs, etc. The entire rehab industry is a scam and just another example of why our health systems are way too costly. Toxic, elitist, inward-gazing, uncritical professional cultures that depend on members who agree to being complicit in order to feel important and needed. Time for reform.