Personal trainers are not nutrition experts, believe it or not. This isn’t a surprise to many of our readers. But we need to shout this from the rooftops so that anyone considering hiring a personal trainer knows what to expect.

Some new research has highlighted just how personal trainers stack up to general public, when it comes to nutrition knowledge. And it turns out they are no better than many of the people who are paying them.

We discuss this research below.

What do we already know about personal trainers and nutrition?

Many clients that employ a trainer expect nutrition advice. A small study from 2014 showed that almost 40% of Australians surveyed had used a personal trainer for nutrition advice in the past. And only 12% of people considered trainers to be an untrustworthy source of general nutrition advice.

So there’s clearly a demand for personal trainers to provide this advice.

And of course, trainers try to meet this need. But as we’ve discussed previously, personal trainers don’t receive a lot of education in nutrition. And when they do try to learn more on their own, they often don’t make good choices for the sources of information they use.

But trainers also are also very confident.

Personal trainers sometimes have opinions of their abilities that don’t match the reality. They can be highly competent, but they’re rarely genuine experts.

This has been shown in a number of ways. Personal training students in the UK were so confident in their abilities that they considered themselves more knowledgeable than their instructors. They admitted to intending to practice in a way that was different to how they were taught, and only provided the instructors with answers that they knew were expected, rather than what they thought to be correct.

And Australian personal trainers have expressed high levels of confidence in their nutrition knowledge and professional skills. Trainers with degree qualifications, and more years of experience, had more confidence.

However, trainers with more experience are usually no better than less experienced trainers when it comes to knowledge. But we often assume that they are.

So trainers are highly confident, but don’t receive a lot of education in nutrition. And many get their information from questionable sources. So I’m not filled with confidence about the state of a trainer’s nutrition knowledge.

How good is the nutrition knowledge of personal trainers?

Dr Mark McKean, who has previously researched personal trainers’ nutrition practices, and his colleagues published some recent research assessing the nutrition knowledge of personal trainers. They were compared to the general public, and dietitians.

The test used had sections on the Australian Dietary Guidelines, the nutrient content of foods, skill in making healthy everyday food choices, and the diet-disease relationship.

A quick refresher on personal trainers’ nutrition scope of practice

The nutrition scope of practice for fitness professionals is entirely defined by the Australian Dietary Guidelines. As someone teaching nutrition to personal trainers, this is the source I refer to more than anything else when preparing teaching material.

Rather than prescribing specific diets and meal plans, personal trainers can provide general healthy eating advice. This does not include advice about specific nutrients. So this questionnaire included information both within, and excluded from, a personal trainer’s scope of practice.

A personal trainer’s nutrition scope of practice can include healthy meal and snack choices, and appropriate serving sizes. Most of us don’t need to get more complicated than that.

In areas within the scope of practice personal trainers scored no better than the general public (both getting about 80% of questions correct). And as expected, trainers were significantly worse than dietitians. In fact, the only section where personal trainers did perform better than the public was in the nutrient content of foods, where they got 81% of questions correct, compared to 76% for the public.

What does this mean?

Now interpret this while keeping in mind what previous research has told us. Trainers often operate outside their scope of practice. This has been identified through self-reported data, and an audit of fitness business websites.

And as mentioned above, many personal trainers use poor sources of information. So if a trainer is using private study to inform the practice outside this scope, we don’t know if it’s good information they are accessing. Finally, we’ve just identified that their knowledge is essentially no better than a member of the public’s.

Naturally the public expects quality nutrition advice from a personal trainer. But we need to be careful that this advice is general in nature.

What advice should personal trainers be giving?

A trainer can still achieve great results with a client looking to lose weight, even though their advice is general.

Substituting energy dense snack foods with healthy options is great advice. The trainer can even provide examples that match the client’s pattern of eating. And increasing fresh fruit and vegetable intake is always a good idea, and can displace higher kilojoule, less nutritious options.

These are both examples of the advice I frequently give as a fitness professional.

Combined with exercise, we will get a decent weight loss effect for most people, most of the time, if they can make these sorts of changes. If this doesn’t work? Or if the client has specific needs, or medical issues? Refer to a dietitian.

Dietitians may not need to make things complicated either, but they have a broader, and deeper scope than personal trainers. They can usually handle the dietary needs to children, the elderly, athletic populations, and those with chronic illness. Image by Rachel Ponder, APG News, CC BY 2.0

Some nutrition training doesn’t mean trainers are experts

The first thing we need to do is more sure more trainers are aware of, and feel bound by, their scope of practice.

Many don’t register with a peak body, and complete the professional development this requires. Some don’t even seek proper qualifications. Others may be registered and qualified, but not be aware of their scope of practice.

Worse, some may be aware of the scope of practice, but think they are better than those other trainers, and think these restrictions shouldn’t apply to them. This is a cognitive bias known as the “better-than-average effect“.

Let’s take a tangent for a quick statistics lesson

If we put 100 personal trainers in a room, and ask them to raise their hand if their nutrition knowledge is better than the average trainer, how many would put their hand up?

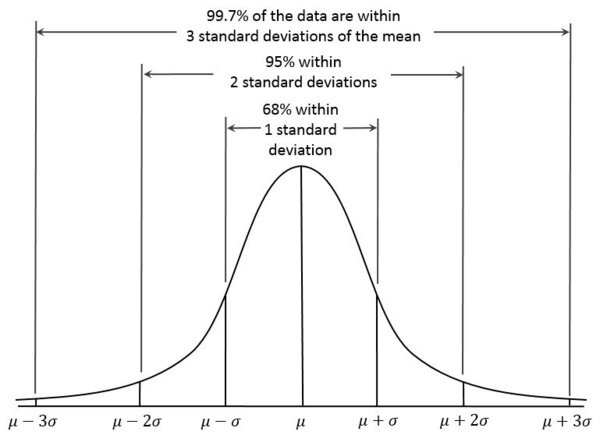

In a normally distributed group, only 13 of them will be significantly better than average, while 68 will cluster around average, and 13 will be worse than average. I bet we see more than 13 hands though. We’d probably see more than 50.

This is a normal curve. With lots of things we measure in life, we are pretty close to average most of the time! Image by Dan Kernler, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normal_distribution, CC BY-SA 4.0

So trainers could do with some damage to their confidence. Misconceptions in the knowledge of personal trainers are common. If you are reading this, and you are personal trainer, just remember that a little doubt can go a long way. Check your assumptions every know and again, and you’ll be surprised how much you can learn.

But, if you are a personal trainer who think the Australian Dietary Guidelines are part of a global conspiracy to encourage the high consumption of refined sugars, and hides the truth that [insert fad diet here] is the only path to true health, you probably didn’t make it this far into the article. And you’re wrong.

Public education about personal training

Part of the reason the public expect nutritional advice from a personal trainer in more detail than this may be a lack of awareness of the role, and education, of a trainer. If we can change this, then trainers may not feel obliged to offer services outside their scope of practice.

So we need to make sure that clients are aware of a trainer’s scope of practice, as well as the trainer.

For the same reason as you don’t ask an accountant to service your car, or a doctor to do your taxes, you shouldn’t be asking for detailed or complex nutritional advice from a personal trainer. Chances are they just don’t have the skills.

I totally agree with this line of thought and would love to have a further chat about this if possible. Some trainers use this a a tool to get clients and provide not so accurate info, because they forget it’s not their role.

Thanks for reading Bruce. Feel free to send a message from the website, I’m always happy to chat.