The verdict is in, and it isn’t good: recent research has shown us that only about half of personal trainers use reliable sources of information. For those of us who want to be taken seriously as personal trainers this is concerning. For those of us who want to know that they are hiring a competent, knowledgeable professional, this is also concerning!

This was first identified in Australian personal trainers in 2017, and has been confirmed by my own research. Other research has identified a higher number, but large proportions of these trainers also used unreliable sources, so this may not be any better.

What is the quality of your sources of information? Do you even notice? Many trainers make poor decisions about what sources to use…

This isn’t a surprise, and is consistent with broader issues in the industry, such as trainers having difficulty identifying reliable sources, and operating outside their scope of practice (something that has been identified again, and again, and again).

But the interesting question is why trainers choose these sources?

Imagine this

Here’s the scenario: you are discussing exercise programs with another trainer at the gym, who is a big guy, when you work out that you disagree about something.

When training for muscle hypertrophy (increasing the size of a muscle), he programs 15 repetitions for each set. Anything more or less, and you won’t get as much of a benefit, he tells you. But you recall that when you were studying your lecturers and textbooks suggested that the 8-12 reps range was best for increasing muscle size.

So you ask more questions. It turns out, this trainer ignores the books and the lecturers. He learnt from another, older trainer, who was also really big, who recommended 15 reps. It must work, because both of these trainers are really big, so it doesn’t matter to them what the books say.

I know… some of you won’t have to imagine very hard in this scenario. You’ve probably seen or heard something similar.

Our choices about what information to trust, and what to ignore, are not always rational

Why do trainers choose to trust some sources, but not others? What is it about this muscle bound trainer that makes him think another person’s opinion is more compelling than thorough academic research? Is research evidence more trustworthy than our personal experience, or the experience of someone we know?

Why is personal experience so convincing?

When it comes to how we expend mental resources, people are cheap.

The term used in the psychology literature is “cognitive misers“, and none of us are exempt. We spare cognitive resources where possible, and make quick decisions, without a lot of conscious processing.

Like a certain one of my friends when it comes to buying a round of drinks, most of us don’t use mental resources unless we have to!

Sometimes this is really useful. When your life is threatened, every second you spend thinking about the threat could be fatal. But weighing up the quality of a piece of information is different, and we usually don’t spend the time on this task that we should.

The cognitive shortcuts we use to speed up processing are called heuristics. These are usually really useful, as they stop us from having to interpret everything we see as if it was brand new. We rely instead on previous experience to provide context to new experiences.

But some of these heuristics can affect how we perform complex tasks, like assessing risk, or the quality of information.

An example is the availability heuristic. We are heavily influenced by the things that happen to us, or the people we know. For example, we might rate the likelihood of certain injuries to be greater if we have seen them or suffered them ourselves. Conversely, we may under-estimate the risk of heart disease, because it doesn’t run in our family.

While it’s useful to be able to recall things that happen to us more readily that what happens to others, we are also more influenced by events that involved celebrities. That isn’t helpful!

And these heuristics can lead to irrational, or inaccurate, thinking strategies known as biases.

Two biases we should know

The first is the primacy effect.

When we collect information over a longer period of time, the information we are exposed to first is given more weight than what comes after. In our current scenario, the older mentor provided some early information, which is considered more valuable than it should be.

And once our opinion is formed, new information is interpreted based on how it agrees with this opinion. When the new information confirms our opinion, we find it more compelling. When it disagrees with us, we are more likely to find reasons not to trust it, no matter what the quality of the evidence is.

This is called confirmation bias.

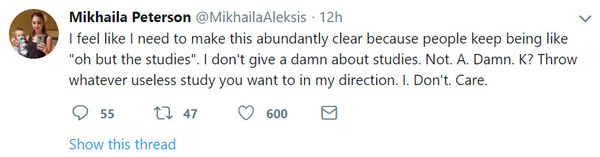

We can see some stunning examples of this online, as we’ve discussed previously.

An example of confirmation bias from Twitter

This explains why it is possible for two people to observe the same thing, and draw completely difference conclusions. So much depends on our experiences before then.

In a rapidly changing field of knowledge this can be a problem. Personal trainers may need to adapt, and modify our opinions to reflect the changing state of knowledge.

Are you rejecting new information because it is wrong, or because you give undue weight to the course you did 20 years ago? Science can change a lot in this time, and exercise and health are rapidly developing fields. Our professional practice should be informed by this changing evidence.

What does this mean for our colleague?

To recap, he is convinced that 15 reps is absolutely ideal for building muscle. After all, he’s lifted for years and years, and he’s huge. And the older trainer at the gym that taught him all those years ago told him that would work, and it did! Fantastic!

Is this reliable? In the eyes of the people involved, absolutely.

He’s bigger than you. How can he be wrong?

But think about how many other variables can effect this outcome. There are nutritional & quality of life factors, and genetic factors, that influence this outcome. There are also a range of other exercise variables, such as exercise choices and training intensity, that we need to consider

It’s impossible to separate the impact of the rep range used from the influence of these other factors. But our biases mean we might credit the rep range with far more importance than it deserves.

Is research evidence more reliable?

In this case, yes. After all, these other trainers don’t know how big they could have gotten using another rep range, while keeping other variables the same. If they’d performed 8-12 reps they might be bigger! But they can’t go back in time to try it, so they’ll never know.

Research is less compelling and interesting, for sure. But a well-designed piece of research can remove, or reduce the impact, of many of the variables mentioned above. This means we can assess the impact of the variable we are interested in with less interference.

Then when we look at the whole body of research, we get an idea of what other researchers have found. Different studies will look at different populations, in slightly different ways, but in the same controlled manner, removing unwanted variables.

Over time (and this can take a long time, sometimes decades!) we see a consensus emerge, and most of the research will suggest the same thing.

You may not have the time to review years and years of research, and assess its quality. That’s why it’s useful to look for those that have done this for us.

You don’t need to reinvent the wheel. When someone highly qualified has interpreted research evidence for you, listen to them!

What does the research on repetition ranges say?

It turns out that this is a lot more flexible than you, or your colleague thought.

A few years ago it was thought, as summarized by Brad Schoenfeld, that moderate rep ranges (8-12) were the best choice for muscle hypertrophy. But the research since then has not clearly supported this.

In fact, research has demonstrated that while for other adaptations (such as strength) we may need to be more specific, for hypertrophy a broad repetition range is fine. Schoenfeld’s own later research showed that 25-35 reps was as effective as 8-12 reps in building muscle in experienced trainers.

The most recent research suggests that training intensity is more important than the rep range used. Just this year Schoenfeld expressed a different opinion to his earlier one (a sign of a good scientist when faced with changing evidence): total training volume seems to be more important than repetition range for muscle mass.

A good, up-to-date review of the current evidence can be found here. In summary, train hard and train frequently. The rep range doesn’t matter as much as we used to think!

Will this change anyone’s mind?

Alas, it might not. A symptom of confirmation bias is looking for ways to reject the contradictory evidence. In this case, your colleague may point to small sample sizes, short training programs, and exercise choices he disagrees with as reasons to reject the research. To someone else though, this research is clearly more rigorous than one person’s experience, which they may not even be remembering clearly.

You may want to agree to disagree. But if you’re respectful and polite about it, and in this case are willing to admit your own error and adjust your practice, there’s a chance that he’s more open to discuss similar evidence next time.

Recent Comments