It’s hard to read research. The language is tough, a lot of specialist knowledge is required, and the statistics are baffling.

But often research makes it into the public sphere. The more controversial it is, the more likely you will notice it. And when this happens, you may debate it with others. You may share articles, or comment on them online. You may provide your opinions, even going as far as to criticize the results, their interpretation, or the methods used.

But do you know how to criticise this research properly? If you have no experience in this field of research are you able to identify problems, and provide an accurate interpretation?

And are you able to read research fairly, and without bias?

The truth is, you’re probably getting a lot wrong.

Why treat research differently to other professions?

I rarely critique the work of my mechanic, or dentist, for example. I just don’t know enough. If I tried, I’d sound like an idiot pretty quickly once we got past a couple of basic concepts. So in the end, I need to trust them to do their job.

This guy doesn’t care what I think of his workmanship… just like I don’t care what he thinks of the quality of my research!

And advances or controversy in dentistry rarely blow up the interest. But exercise or nutrition? Different story!

The casual reader can miss a lot of the finer details of research papers. This means the limitations of the research aren’t well understood, and it ends up being interpreted in a way not intended by the researchers.

Then these opinions get shared on social media a few times, context is lost, and some conservative, uncontroversial research leads to myths and misconceptions spreading.

So today we’re going to teach you the basics of how to read a research paper. At the very least, you should finish this article understanding that maybe you don’t know as much about research as you thought. If that makes you pause before commenting next time, that’s a great start.

Can we get away with just reading the research abstract?

Please don’t! The abstract gives us a brief rundown of the background to the research, the methods, findings, and conclusions. But it’s really brief, sometimes only 150 words.

The abstract does not tell you everything you need to know about the paper. But it does help you decide if you want to read more of this research or not. If the abstract looks relevant, you then continue to the full paper.

Just like seeing the trailer of a movie doesn’t mean you’ve seen the movie, reading abstracts doesn’t mean you’ve read research. You’ve just looked at the trailer!

So you shouldn’t just stop at the abstract, unless you only need a very cursory understanding of the paper.

This is a problem if you don’t have access to the paper, as most journals are behind paywalls. Then you can only read the abstract. Don’t comment, no matter how much you want to!

How can I read research papers if they are behind paywalls?

Many are behind paywalls, but not all. These days open access journals are more and more popular.

There are ways past paywalls too. Researchers are usually permitted to share their own work with their colleagues, or by request. This is done online on sites such as ResearchGate (kind of like a nerdy Facebook for scientists).

Articles posted on ResearchGate are usually searchable online. And if there isn’t a copy available, you can contact the author.

Believe it or not, researchers usually love it when people show an interest in their work… if you talk about it fairly. It’s hard enough to even get their colleagues to pay attention, so some public interest is usually very welcome.

Academics don’t get out much. A little attention for their research is usually very welcome

Reading the introduction

Once you get hold of the full paper, you can dig our teeth into the detail! You’ll probably start with the introduction.

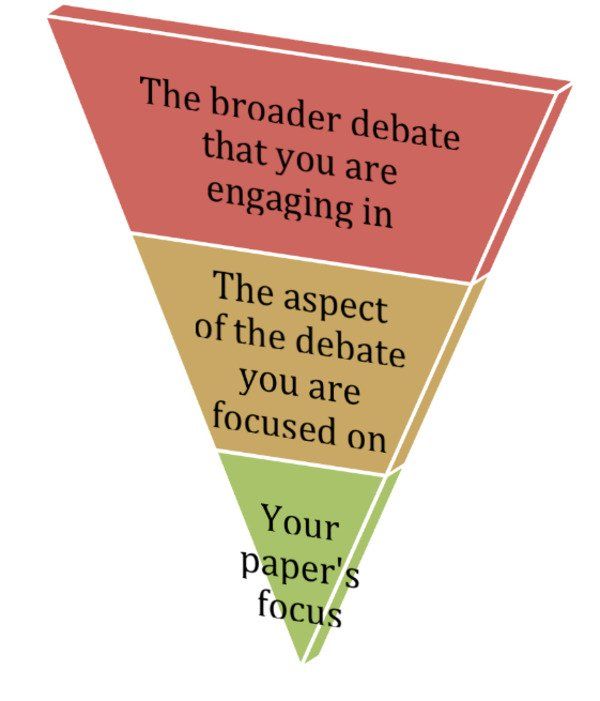

This is where we learn about the research that came before this paper, and the questions that are still to be answered. If you look carefully, you will notice a specific structure when reading a good introduction. *

First is a broad introduction to the topic, and some fundamental concepts. This is written very carefully, and other research should be referenced any time a specific claim is made.

Then the attention of the paper will narrow, into the area the author is interested in. Then it will identify what gaps exist in our knowledge, ** before focusing on the question to be answered by this research.

We can visualise the introduction having a structure like a funnel. It starts broad and shallow and gets more and more specific as it goes.

The funnel of a research paper’s introduction. Image by Sherran Clarrence, https://phdinahundredsteps.com/. Used under creative commons license CC BY-SA 4.0

The end of the introduction explains exactly what the study is about. This could be in the form of a hypothesis statement – the author may make a prediction, that they attempt to test with their research. ***

If they haven’t made a prediction, they’ve clearly identified what they want to learn as a result of their research.

Reading the research methods

If you’ve read research on your own until now, this is a section you may have been skipping over. But it’s important, because it tells you a lot about the quality of the research, and what you can interpret from the findings.

If you’re following along on an actual paper, from this point on the headings might get a little different from what we discuss. That’s because different journals require different formats. There are a few popular styles, with one of the biggest coming from the American Psychological Association.

There are usually several subheadings in the methods, which cover a lot of information.

The design of the research

This is a crucial detail that amateurs often miss, because different questions will be answered using different types of research. And some study designs that are considered gold standard for one question, are useless for another. So it’s not as simple as describing a study as “good” or “bad”. I’ll explain…

We often refer to the “gold standard” of research being the double blind, randomised control trial (RCT). This is where participants are allocated into either an experimental group, or a control group (that gets a placebo). Neither the researcher, nor the participants, know which group they are in. If they are especially careful, the researchers don’t find out which group was which until after the data was analysed.

In a placebo-controlled trial the participants don’t know if they are getting the treatment, or the fake. Just expecting an effect can lead to one, so we need to make sure this effect doesn’t influence our results.

Why don’t we used double blind, randomised control trials for everything?

For lots of reasons. Sometimes blinding is impossible. If you are comparing two different types of exercise, you can’t disguise what exercise the participants are involved with. It’s also hard to blind someone to the type of food they are eating! But when testing supplements or medications, the double-blind RCT is often the way to go.

Sometimes other approaches are better, like a cross-over trial. That’s when the participants are exposed to both the conditions you want to compare, with a recovery period in between.

A cross-over study is useful because we end up with identical groups – because the same people are in both groups. This removes a lot of variables. But it has other disadvantages, and can’t be used if what we are measuring will have a lasting effect on our participants.

As long as we have a placebo control though, right?

Actually, sometimes we don’t even want control groups. Sometimes having a control group is unethical. If you want to know if a certain medication works, for example, you wouldn’t have a placebo group to withhold medication from – that could be really dangerous. Instead, your comparison group might get the normal treatment of the day. That would then be compared to the new treatment.

Participants in this research completed a challenging exercise protocol in different states of dehydration. It’s hard to blind participants to how much water they drink! And this wouldn’t help answer the question being asked, so we need to design this research differently.

Another example where we don’t use control groups is much of nutrition research. Some people who read research into nutrition constantly criticise it for being poor quality, but think carefully about this. If you want to know what the long-term effects of high or low amounts of a nutrient are, we need a long-term study. We need to assess health over decades, and even look at death rates.

Clearly, we can’t run an intervention for that long. And if we could, it would be unethical to deprive someone of a nutrient that gave them an obvious health benefit, for the sake of clean data.

Instead, we may rely on population data. We find groups of people with historically high and low levels of that nutrient and compare them. Or we ask people what they eat, and try to work things out from that.

Of course these approaches are limited. We all know it. But until we have a better way, that’s the best we’ve got. This isn’t a reason to disregard nutrition research to suit your biases.

Some of the same people who bash nutrition research for being unreliable are happy to embrace animal studies or personal anecdotes that back their opinions. Be consistent when you criticise research.

What should we take from the study design then?

The important thing is that the design of the study is a good way to answer the question being asked. Different questions need different approaches.

If you don’t have training in research methods, and know what approaches you could choose from, you probably won’t know if it’s a good paper or not. If you can, ask an expert!

Participants

This is also important because this paper’s findings may not apply to anyone other than the group assessed. The smaller the group, and the more alike participants are to each other (homogenous), the less we can apply these results to others. But it’s easier to get clear results.

So one paper may not tell us much. We might need to look at a range of research, using different participants, to get the full picture. This research might not all agree, but hopefully it reaches a broad consensus.

Exercise research is a good example of research that can’t automatically be applied to young and old, male and female, elite and amateur. We need to do research on all these different types of people to draw a broad conclusion.

How many participants were used?

The amateur reader is usually under the assumption that more participants means better research. It’s by far the most common criticism of research I see. But it’s far too simplistic.

Sometimes the study design means you can use fewer people. My master’s research, for example, used a crossover design, with three different experimental conditions. I only had 14 participants, but each took part in all three conditions (in a randomized order) and acted as their own controls. So I had the equivalent of 42 participants, but with fewer variables to mess things up.

But I’ve done other research that needed hundreds of people, like when doing a cross-sectional survey. The numbers depend on the study design, and the statistical tests you want to use. Different tests need different numbers.

But larger numbers may make it easier to get positive results in some tests. Stacking your research with more participants than you need is usually frowned upon, as it can be a way for your results to look better than they are. It’s also unethical to test people when you don’t need to – you’re imposing on people for no reason.

Instead of thinking “more is better”, we should be thinking “did they have enough” participants for their study?

Who were the participants?

We’ve mentioned this above, but this is really important in exercise and nutrition. Younger people are different to older people. Men are different to women. The education or income of participants might change things, and so might ethnicity.

A group in which everyone is very similar gives us cleaner results. But a more diverse group gives us results we can apply more broadly. There’s no right or wrong approach here. But we should know that the right approach is taken to answer the question, and fit the study design.

The mistake is to take results from one population, then try to apply it to other populations, without knowing if this is appropriate or not.

Materials & procedures

These are usually subheadings of the methods that tell you what equipment is being used, and how tests are conducted. The idea here is to make the research replicable. In theory, another scientist should be able to read this research, and copy the methods exactly.

In reality, this may not be the case. Journals have strict word limits, and sometimes the messy details of research are glossed over. But these sections will tell you how careful the researchers were, and how they controlled other variables.

Just like other occupations, researchers have different strengths and weaknesses. Someone who has a strong understanding of statistics will get a lot of questions their colleagues!

But again, it’s hard to read unless you understand the field. And even in your own field of research, there will be tests and methods you’re not familiar with. You may need to read up on these.

Reading the data analysis

If you thought we were getting complicated before, hold on. Without post-graduate study in statistics, this section of a paper may not make a lot of sense.

For different study designs, and different types of data, we have different types of analysis. This section should tell you exactly what analysis was conducted, what they consider a significant result, and even what software was used.

But there’s lots of variety between fields here. In psychology for example, every statistical method used will be listed here. In other fields, they may just describe the major ones.

What you are looking for is whether the analysis described is a good way to test the hypothesis. And some of the key words from the hypothesis will help you here.

For example, if the study is looking for an association between two variables (that is, two things are likely to occur at the same time), they may use Pearson’s correlation. But if they want to identify a possible relationship between the two (that one causes the other), then a t-test may be used, or an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Again, the exact choices depend on the design of the study and the type of the data.

Reading the research results

Once our data is analysed, we see the findings reported.

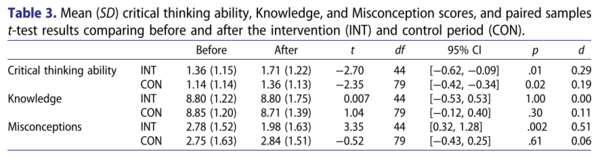

Important results will be reported graphically, or in a table. This helps them stand out from the text, so you can go straight to these if you want to. Less important results will be reported in the text.

But remember there’s no interpretation here. All the authors are doing is reporting their findings, and usually the results of the data analysis. If you know how to read these statistics, you will start to form some opinions in your mind about what these results are showing. Then when you look at the authors’ conclusions later, you can decide if their interpretation is fair.

This is often really hard to read. It’s dry and full of numbers. Even academics’ eyes glaze over at times, and even they won’t always be familiar with the statistics reported.

Riveting, isn’t it? This is how results may be reported in the field of psychology.

Reading the discussion

Now we get more interesting again. The results from the earlier section are discussed, in relation to earlier research, and with some commentary on what it means for future research or practice.

The authors are telling you what their research adds to our understanding of the topic. They might have confirmed or contradicted earlier findings. Or they add a missing piece of detail.

A good paper sets the scene for this in the introduction. The same literature is referred to, but instead of just reviewing it now, we build on it.

Scientists sometimes refer to themselves as “standing on the shoulders of giants”. This is a quote from Isaac Newton, used to acknowledge the contribution of those that came before you, whose knowledge you are building on.

Even if you contradict prior research, it doesn’t mean they were wrong, or incompetent. It just means they did they best they could, with the knowledge, equipment, and procedures of the time.

If you pay attention, you will notice something familiar about the discussion. It will start with a summary paragraph of their findings from the results section. Then we see the funnel again, this time in reverse. We start narrow, talking about what our major results mean. Then we move to our minor results, and discuss what our findings mean more broadly.

Reading the conclusion

This is where we put our key takeaways. If you are not interested in the nuts and bolts of the study, you can skip straight to this. It’s brief and may include some useful recommendations.

But if you do this you’re trusting the authors to be rigorous in their methods, and reasonable in their findings. If you want to analyse, or be critical of research, you shouldn’t skip the detail of it.

But I don’t trust scientists!

Why not?

I hear criticisms about science, and scientists from people outside academia all the time. Especially from those whose ideas are not supported by research.

“Academia is a closed shop. They’re afraid of new ideas, and just support each other. They’re all paid off by Big Pharma, and want to keep you sick to make more money”

But as you’re hopefully starting to realise, research is really hard. So is reporting it. To be able to prove a new idea takes a high level of evidence, and individual experience of traditional remedies (just to pick an example) often don’t stand up to this scrutiny.

We use this experience in research sometimes – they’re called case reports. But they don’t provide the same level of evidence as some of the other methods we discussed earlier.

Distrust of scientific research is particularly obvious in anti-vaccination activists. But this usually comes for a lack of understanding. Accusations of a conspiracy is a far quicker way to discredit research you don’t like than actually trying to understand it.

There’s no research on my particular brand of crazy… it must work if they haven’t proved it wrong.

Slow down there, turbo. That’s not how it works. The burden of proof is on the person making the claim, as brilliantly illustrated by Bertrand Russell’s famous teapot.

It’s not up to anyone else to prove you wrong. It’s up to you to prove your claim if you want to be taken seriously. And the more unlikely the claim, the better the quality of the evidence we will need to accept it.

Russell’s Teapot, by Alex Zak, used under creative commons license CC BY-SA 4.0, and cropped for size. If you look closely you will also see Occam’s Razor, a flying unicorn, and the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

So can you read research?

Maybe reading this article has given you a little doubt about this. And it should. A lot of things look simple when looking on from the outside. But they get more complicate the more you know about them.

Research is one of the more extreme examples of this. It’s in the public eye, as the media often reports on it. But it’s so difficult that it takes nearly a decade of education and training to prepare you for it. So a lot of the finer details pass the casual observer by. No wonder we get into arguments online.

Luckily, we have a simple 8-point checklist below. If you can say yes to most (or all) of these questions, then you’re ready to interpret research correctly!

Your research reading checklist… do you know what you’re reading?

- Do you have enough education in the field to understand the paper? A relevant degree would be a good start. A research degree, even better.

- Have you done some research of your own? Nothing helps you understand the challenges and processes of research like going through it yourself. Give yourself a bonus mark if your research is in this field.

- When you read the introduction, are you familiar with the research cited? You should know who the key authors are, and the key references.

- Do you understand the methods chosen? And can you tell if they are a good way to answer the question being asked?

- Are you familiar with the tests and equipment used?

- Do you understand the statistics used? Are they an appropriate way to answer the question? Can you tell if there is a better analysis, or if the authors have not reported something?

- Can you read the results section, and stay awake? Or do you find your eyes glazing over, and you start skipping over detail?

- Can you tell if the authors have interpreted their results correctly? Or are you taking their word for it.

What if I didn’t pass the research reading checklist?

Take your hands off the keyboard. Don’t comment on that research! Don’t start an argument!

There are some places to go online, and people to talk to, who will interpret research for you within a field. So ask for help.

Who can you ask? Us, for a start. The goal of this site is to spread critical thinking skills to the public, especially in the areas of health, exercise, and nutrition. So send us your questions.

Or, search for sources that have already interpreted this information for public consumption. National dietary guidelines, for example, are a brilliant summary of large bodies of research, interpreted by experts, simplified for public consumption.

Don’t like that statement I just made? Maybe have a look at that checklist again. Or read this.

What if I don’t have a degree?

It helps if you do, but it doesn’t mean you can’t learn to read research if you don’t. All the information from a higher degree, in almost any field, is all freely available online. You could teach yourself to the same level as a doctorate if you had the time and inclination.

But it’s harder to do, because you need to sift through a lot of bad information. You won’t get as much help, or get your questions answered. It won’t be presented to you in a sequential, logical way. You won’t get tested on your knowledge to identify weaknesses. And you won’t learn some of the tricks of the trade that an academic supervisor could pass on to you.

So if you want to learn how to read research well, this article is just a start. You’re welcome to go further, but hopefully now you realise it’s a long and difficult process.

* don’t get me wrong, there’s lots of bad research, particularly in predatory journals, that publish almost anything for a fee. And there are some researchers who just suck at academic writing (like me). But this is how it should look.

** it’s a common accusation of scientists that they are arrogant know-it-alls, who don’t accept new ideas. This couldn’t be further from the truth, and betrays the lack of understanding of the person who makes this claim. Science is the constant search for answers to our questions. If we knew it all, why bother with research?

*** if you want to get super nerdy here (and why wouldn’t you?), you may like reading about the null hypothesis.

This is a nice article, a very good overview, but I have to comment on one claim you make.

> For example, if the study is looking for an association between two variables (that is, two things are likely to occur at the same time), they may use Pearson’s correlation. But if they want to identify a possible relationship between the two (that one causes the other), then a t-test may be used, or an analysis of variance (ANOVA).

I don’t think this is correct. You can use an ANOVA to test a naturally occurring relationship between a categorical variable (say, gender or nationality) and a continuous outcome, without making a claim that one causes the other. ANOVA isn’t just for experiments. And you can use a correlation to test a relationship between two continuous variables, if your method establishes that the relationship is causal (for example, X varies at random and plausible confounds are controlled for). These stats methods are chosen because of the nature of the variables they involve, not the nature of the methods they test.

Thanks for contributing Roger, your thinking around stats is more nuanced than mine! I’ll incorporate your feedback when I eventually get around to updating this article.