I know, it’s a provocative headline, but it’s right. Personal trainers, along with doctors and other health professionals, have a bias against obesity. And this has been shown in research.

And it’s not just professionals. The general public, and even children, have also demonstrated this anti-obesity bias!

Today we discuss what the research tells us about this bias, what this means for personal trainers, and their clients. We also discuss how it can be overcome.

Just one of the signs of an anti-obesity bias is how hard I found it to get free stock photos of overweight people…

The business of weight loss

It’s clear that obesity is a massive issue. Our health is effected, and the impact on the public health system is massive.

The foods and drinks that contribute to obesity are big business, and well-advertised. And so are the weight loss programs that are promoted in response. Personal trainers are part of this weight loss response. For most trainers, those wanting to lose weight are an important part of their client base.

But most people fail at weight loss more than they succeed. So people keep looking for answers, and seeking help.

What advice should we be getting?

But people looking for help don’t always get the best advice. They could be exposed to nonsense about fasting, detoxes, and juice cleanses from social media.

And personal trainers could do more harm than good. They could prescribe ineffective exercise programs. And they may prescribe diets that are too restricted, exceeding their scope of practice in the process. This could even lead to worse outcomes in the long term. Exercise physiologist Dr. Bill Sukala explains:

You can simply starve yourself on a fad diet and “lose weight” on the bathroom scale but, in actual fact, the majority of that weight loss will be water and valuable metabolism-stoking muscle. You will lose a little body fat but not nearly as much as you expected.

The dirty secret of the so-called health industry is that quick-fix diets and “fat burning” supplements are not sustainable and they set you up for failure. In time, you’ll eventually gain back all the weight, and probably a bit more in order to protect against future weight loss attempts.

The best available evidence still supports the age old wisdom that you need to move more, and eat lots of fruits and vegetables.

But sometimes this simple message gets lost in the noise around us.

Forgo fasting, fad diets and detoxes in favour of moving more and improving your nutrition.

How can a personal trainer help?

A personal trainer can be really helpful with weight loss attempts. Their scope of practice includes prescribing and supervising effective exercise programs, encouragement, motivation and support, and providing basic healthy eating advice.

And for most people, this is more than enough to help achieve a weight loss outcome, if they can stick with it.

We’ve provided advice about how to choose a personal trainer elsewhere. Making sure your trainer is aware of, and sticks to, their scope of practice is hugely important.

A personal trainer, who relies on clients wanting to lose weight, and practising within their qualifications and experience, is going to be supportive of their client. A good trainer will be empathetic, encouraging, and have faith that their client will give weight loss their best attempt.

A good personal trainer will be empathetic and encouraging

But an obesity bias effects all of us

A bias is an inappropriate weight of opinion either in favour, or against, a group of people or an idea. It’s a topic that comes up a lot on this site. In fitness, personal trainers may be biased towards a certain style of training, or against another. Or towards a certain pattern of eating.

An obese person experiences bias that their average weight friends will not, if all other things are equal. This could be an implicit bias (such as feelings someone has that they don’t express), or it could extend to our actions and behaviours.

This bias even influences how we treat the people we love. For example, Parents will provide less financial support for college on average for overweight children!

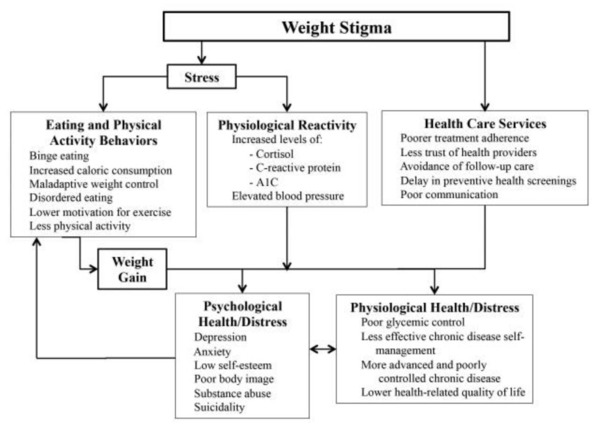

The stigma associated with obesity can have its own complications for mental and physical health. These can make weight loss even more challenging.

The effect of the stigma associated with obesity, from Puhl, Phelan, Nadglowski & Kyle (2016)

Even health professionals?

You would hope that health professionals would not have this bias. After all, they spend a lot of their time helping overweight people. Unfortunately, they are not immune.

Anti-obesity bias has been shown in the medical community repeatedly. Medical and psychology students demonstrate this bias, and even doctors and researchers that specialise in obesity. And it’s been shown repeatedly. Thankfully this bias is usually implicit, and doesn’t affect how people are treated.

Are personal trainers different?

Do personal trainers possess a bias against obesity? Surely not! After all, someone wanting to lose weight is a trainer’s bread and butter. The fitness industry wouldn’t survive without them!

Part of the rationale behind having a trainer is the care and attention they can provide. A client could get an hour of one-on-one attention and advice, instead of a much shorter doctor’s appointment, when more pressing medical issues mean that exercise and nutrition don’t get discussed.

Trainers should be welcoming overweight clients with open arms. They can provide safe, effective training, and simple nutritional advice, to help them improve the health, and lose extra body fat. How could they be biased?!

What does the evidence say?

Unfortunately, trainers probably are biased. I’ve so far only found two studies looking specifically at personal trainers, but the results are clear.

The first compared a group of personal trainers to regular exercisers. They tested both explicit beliefs towards obesity, as well implicit bias (by assessing word associations with either fatness or thinness).

Both groups showed explicit and implicit anti-obesity bias. They considered, for example, overweight people to be lazier. And if the person surveyed had never been overweight themselves, the bias was worse.

Trainers also had more bias if they considered that body weight was dictated more by self-control, than by the combination of factors that can contribute.

Newer research confirms this anti-obesity bias

A more recent study looked at a more qualified group of trainers, most having completed at least part of an exercise science degree. They had an interesting way of measuring explicit bias – actors who were either overweight, or healthy weight, provided information to a trainer in a mock consultation. The trainers’ behaviour was observed during this session.

In contrast to the earlier study, there was no explicit bias towards the overweight actors. Trainers sat the same distance away from the client on average, regardless of their weight. They also gave them the same amount of advice, both in the number of suggestions, and the length of their answers. So trainers provided about the same quality of service.

But, there was still implicit bias. Trainers were more likely to rate an overweight client as lazy after the mock consultation. They also tended to prescribe shorter, less intense training, despite the fact that the actors provided exactly the same information about their ability and exercise history in each condition.

So trainers were professional, and did a good job, regardless of the weight of the client. That’s great. But the implicit bias remained, and influenced the advice they provided.

This bias affects more than just exercise advice!

Students are also influenced by this bias when learning. University exercise science students were surveyed before and after a course looking at a range of weight loss interventions. The course included diet, exercise, medical, and surgical options, and the evidence informing each.

The students entering the course had a strong bias against surgical interventions for weight loss, and strongly preferred diet and exercise interventions. They maintained this after completing the course.

While it’s appropriate for trainers to prefer exercise interventions, there is a point when we need to hand over to, or collaborate with, another professional. Behaviour change is hard, and we know that most weight loss attempts eventually fail. So sometimes other interventions are needed.

Trainers have also been shown to have a bias against other interventions, with one study finding that most trainers thought that their colleagues would tell people not to take medications prescribed by their doctor for the purposes of weight loss. Trainers also rated medications as very unimportant in a list of other options for weight loss.

Lifestyle interventions can be a great approach for tackling weight loss, but they’re not the only approach.

Why did the researchers ask about other trainers, rather than ask the trainer about their own opinions? Because trainers are more likely to be honest about their colleagues, than their own thoughts, particularly when they know they are exceeding their scope of practice.

As a trainer it’s ok to have a preference, and attempt lifestyle changes without medication. It’s not ok for a trainer to exceed their scope of practice, and tell a client to ignore medical advice. At most, a trainer could suggest a second opinion, from someone qualified to provide one.

What can trainers do about anti-obesity bias?

All these results show how strong the stigma of obesity is. It’s something that a fitness professional, or someone that has been not been overweight, may not fully understand. Our fitness professionals need to act with empathy, as Dr. Bill Sukala explains:

A trainer who automatically assumes that their client is overweight simply because he or she is lazy and has no willpower is a cop out. Slowly develop rapport with your clients and build trust. Some clients may be very sensitive and self-conscious of their body, so ask permission to touch your client if needed to correct exercise technique.

They’re used to feeling judged, so it’s important to start out with activities they can accomplish, and progress slowly and steadily (as tolerated) to build up their confidence and self-efficacy. Some individuals with weight issues may be hard on themselves, so be sure to use genuine and sincere praise when they do a good job to help break down any negative self-talk patterns.

The good thing is, most trainers try really hard to do the right thing, and treat their overweight clients sensitively and with respect. But from the research we looked at above, implicit bias is a massive problem. It’s present even when explicit bias is not.

How can we correct anti-obesity bias?

Good news: the research has some answers here. Bad news: it’s not as easy as just trying hard not to be biased. After all, it’s implicit. We think we are being fair, when we are not.

Multiple studies have shown those who weigh more have less anti-obesity bias. But that’s obviously not a great solution, and even the most obese of us still possess this bias to some extent.

Bias is also reduced if you have friends who are overweight. This suggests the bias comes from a place of ignorance. You are more likely to be aware of your friends’ weight loss attempts, work ethic, etc., than you are a stranger’s.

In education, we can focus on the complex interaction of the causes of obesity, including genetic, metabolic, and social factors! Some factors are out of a person’s control, which can make maintaining or losing weight more difficult. Improving awareness of this can help.

When someone is aware of the effort that has gone into weight loss attempts, bias is reduced. We know that most people have made multiple attempts at weight loss before coming to a trainer. Professionals should keep this in mind when providing advice – a detailed pre-exercise screening should cover some of the details of these previous attempts.

Trainers should be empathetic towards clients, and conduct a detailed pre-exercise screening, including information about previous weight loss attempts..

Lastly, people of different weights should be represented in images we use for advertising health and fitness services. After all, most fitness facilities want to attract people wanting to get stronger, fitter, healthier, and lose weight. Including people of different body shapes in promotional material could reduce bias in members of these facilities.

In summary

We’ve identified that personal trainers have biases about the very people they spend most of their time helping. That’s pretty depressing! What chance is there for someone to get treated fairly when seeking help to improve their health?

The first thing to note as that we are obviously not talking about all personal trainers. Groups of people are researched, not individuals.

In any sample of trainers, there will be some who are empathetic and supportive, and also being competent, providing great training and advice. When you find that trainer, hire them! And tell your friends – that is who we need to be supporting in the fitness industry.

Secondly, let’s not judge too much. Everyone has biases, and eliminating them is almost impossible.

Even pointing out a bias, and telling someone to keep an eye out for it, is usually not helpful. The personal trainer we share this article with is likely to identify the bias in someone else, but think it doesn’t apply to them. Ironically, this is also a bias, known as the “better-than-average effect”.

So yes, you probably possess this bias. I probably do too. Your trainer probably does too. But your trainer can still do a great job, be thoughtful and considerate, and work hard to stop this bias influencing how he or she treats people.

Recent Comments